The debate around banning mobile phones in schools is one that sparks strong opinions, and rightly so. As I reflect on the diverse perspectives presented in the class debate and accompanying readings, I find myself both intrigued and challenged by the complexities of this issue. Are we protecting students’ learning environments by implementing these bans, or are we stifling their ability to thrive in a digital world?

Argument for a Ban by Kritika and Meharun: Focus, Fairness, and Mental Health

The pro-ban argument was buttressed with both quantitative research and concrete policy shifts and legislation. The experimental study from Carleton University found that a ban improved test scores among 16-year-olds by 6.4%, equivalent to five extra instructional days.

This was echoed in the agree team’s opening statement, where they argued:

“Phones are not only distractions rather, they are amplifiers of anxiety and inequity in schools. Removing them levels the playing field and creates a focused, healthier environment for all learners”.

However, the strongest argument for me came in the following observation: lower-achieving students improved at higher rates, making this a potential equity and engagement solution, not just a disciplinary one.

New York State and the Australian state of New South Wales (NSW) both implemented full-day cellphone bans using Yondr pouches. In NSW, Principals observed a reduction in behavioral issues and a rise in student learning and positive interactions. The NCES 2025 document supported the widespread agreement among American school leaders. Per that report, over 77% of schools already limit student phone use during instruction. In this dataset, over 58% of surveyed school leaders agreed that “phones have a negative impact on student performance.”

Jonathan Haidt’s TED Talk (2018) was another particularly convincing and visceral argument for a phone ban. In this personal reflection, Haidt diagnoses a rise in anxiety, depression, and loneliness among the youth, attributing these issues to pervasive and perpetual smartphone use. While he does not have a causal explanation for this effect, Haidt frames this as a public health emergency and not merely an education problem. I found myself entirely persuaded. When I think back to my own classes (and check my own behavior), how often do I or do students carelessly let our phones interrupt class? Is it ever just one scroll? I can’t help but feel we are losing more than we are gaining by surrendering our attention. A 2015 analysis by Beland & Murphy, discussed in a Chartered College article, used UK school data to show that phone bans boosted GCSE scores, especially among lower-performing students when enforcement was strict. Yet the article also points out that phones can support key learning activities like collaboration and feedback, and that younger learners appear less distracted by phones, suggesting a more nuanced, age-sensitive approach may be appropriate.

Reflective Insight: From this lens, banning phones becomes an act of service, not of control. It’s about freeing our students from distraction, temptation, and risk. I connected with the central idea that digital boundaries do not create deprivation; they create space for focus, for learning, and for human connection.

Argument Against a Ban: Teaching, Not Taking Away

However, the anti-ban argument also introduced important nuances to my thinking:

Sadi also asked a compelling question:

“What is the role of educators if we eliminate tools like phones instead of teaching students how to use them responsibly?” .

Campbell et al. (2024) published a scoping review of all existing literature on this very subject. They collected and compared 22 studies from 2016-2023, all which addressed outcomes of cell phone bans on academic performance and behavior. Their conclusion is complex and fragmented which included some studies showed positive effects of a ban, some were neutral, and some even showed a negative impact of taking away mobile devices. One important argument that stuck with me is the possible harm to families who may be actively marginalized from digital learning if they cannot access phones. Furthermore, this approach does nothing to inculcate digital literacy or digital citizenship which are key skills in the digital age.

A 2013 meta-analysis by Thomas, O’Bannon & Bolton offers a surprising insight into current classroom practices: many teachers are already fans of phone integration for instruction, citing tools such as polling, multimedia projects, and collaborative learning. Their research found that low-SES students may particularly benefit from classroom phone integration. This study repositions the mobile phone as a possible pedagogical tool.

Clayton and Murphy’s (2016) direct classroom study presents a more inspirational story. In this study, students were asked to create instructional videos for their peers, engaging with multiple mobile applications such as Google Classroom and Khan Academy. The result was more than improved academic performance. Students built media literacy, personal agency, and peer connection and support. This made me wonder if the issue is not the device but how it is (or is not) used in the classroom.

Reflective Insight: From this point of view, bans are quick fixes but band-aids, not cures. Students are unlikely to ever be in an environment without access to a phone. Is it not our responsibility to teach them to live with—and not from—their devices?

The Middle Ground: A Place for Myself

At this point, I no longer see the ban/no-ban issue in black and white. Each side has merits and can speak to different contexts and education needs. On the one hand, phones represent a clear danger to the ability to focus and, by extension, wellbeing. On the other hand, they have clear instructional value when used correctly.

So, how can we serve both values in a coherent policy?

In my opinion, schools can:

1. Set structured restrictions on phone usage during instructional periods, including time limits and designated activities

2. Designate structured periods in the school schedule when students are encouraged to use phones to learn or for homework.

Nofisat

Thanks for your well researched blog Nofisat. You have given great points

for banning phones in schools. I see significant concerns regarding focus, mental health, and equity within my own classes. I agree that teaching responsible use over outright banning is what I lean towards. The “teaching, not taking away” argument resonates with me. I think that its our responsibility as educators to teach digital literacy to our students. I also struggle with this as a parent. As should we not be preparing students how to be responsible with their devises and not just take them away? Mobile devices can serve as a great resource. For example, my students all have smartphones that have a program called nursing central downloaded. It has all the needed information for nursing students at their fingertips…. I has completely changed which resources such as textbooks, manuals etc. that my students have to bring to clinical. They literally only need their smartphones. I know I have older students, but why cant teachers decide what will work in their OWN classrooms. I am on your side when you think being structured and putting restrictions on is the way we should go and NOT banning them completely.

Have a great week!!

Thank you so much for your insightful comment! I really appreciate your perspective, especially coming from both an educator and parent lens. You made a great point about tools like Nursing Central, what a powerful example of how mobile devices can truly enhance learning when used responsibly. Thanks again, and I hope you have a great week too!

Hi Nofisat,

Thanks for your thoughtful and well-cited post. I liked how you entertained both sides of the debate and also reflected honestly on the journey of your own thinking in the process. Your reflection of Jonathan Haidt’s TED Talk was particularly interesting to me because you framed the phone ban as an act of service rather than control. That language is really powerful because it reframed the debate in terms of the care we have for our students. In the debate, it was mentioned that lower-achieving students benefit from these strong boundaries. I reflected on my own teaching experience in this, and I do agree that it is my lower-achieving students who often benefit from strong boundaries. Whether their low achievement is due to behaviour issues or lack of support, having firm rules helps these students regulate better. Sadi’s question of what is the role of teachers, if not to teach students things, including phones, still sticks with me as well. While I do agree it is our responsibility to teach, I wonder if it is our job to teach THAT? Or is that more of a parent’s responsibility? Your suggestion of a “middle ground” is similar to what I think from a teaching standpoint. I wonder if we could give the students some ownership over when and how they use phones in class. Could this promote student engagement since they will feel they have autonomy? Maybe this is the middle ground they need. Again, thanks for your reflection. Your post was insightful and also provides a practical path forward for us as teachers.

Thank you for your kind words and thoughtful reflection! I really appreciate how you expanded on the idea of strong boundaries as a form of care, especially for students who need that structure the most. Like you, I’m still grappling with where that line falls between teacher and parent responsibility, but open dialogue like this certainly helps. Thanks again for engaging so thoughtfully!

Thank you for this thoughtful and well-balanced reflection. You’ve done an excellent job capturing the real tension between structure and empowerment when it comes to phones in schools. As a secondary school teacher, I’ve wrestled with this dilemma in my own classroom. One vivid example comes to mind: during a group project, I allowed students to use their phones to research and collaborate. While some used them effectively to gather information or share files via Google Drive, others quickly drifted into Snapchat and YouTube. I ended up spending more time redirecting than supporting learning. That experience taught me the importance of purpose-driven phone use and clearly defined boundaries.

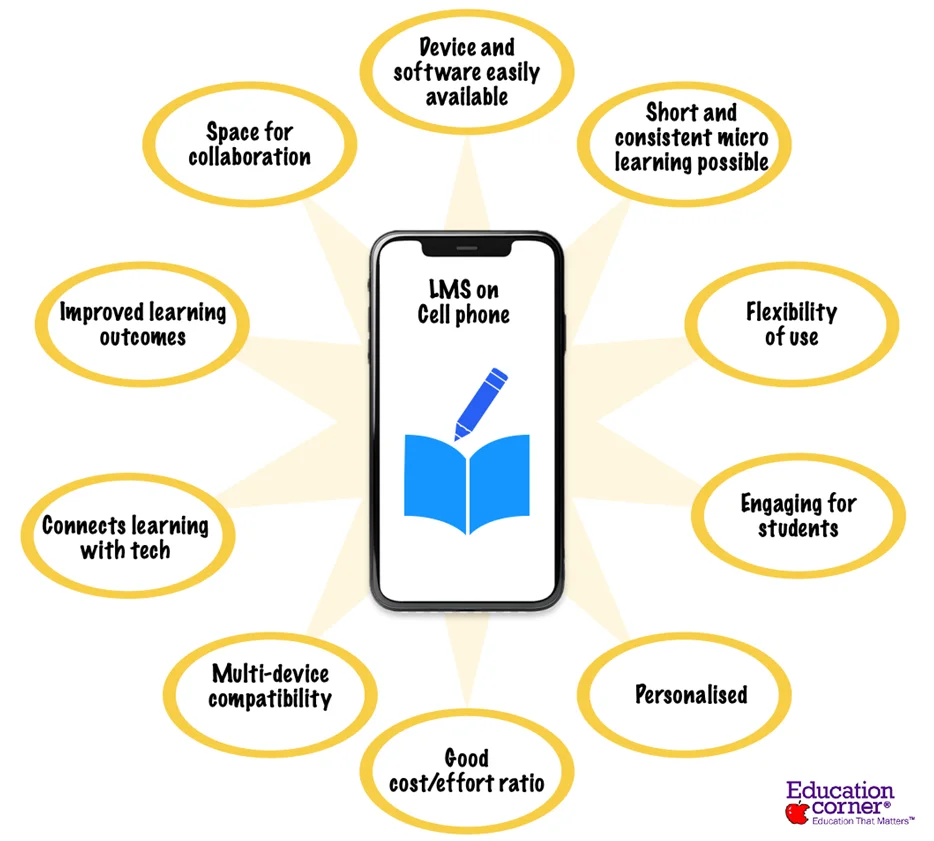

Your mention of structured use really resonates. This year, I tried something new: “Tech Time” at the end of class, where students could use phones for specific tasks like vocabulary review through Quizlet or checking homework instructions via our LMS. Engagement and trust increased noticeably—phones weren’t seen as the enemy, but as tools used intentionally.

Like you, I no longer see this debate in absolutes. Phones aren’t good or bad—they’re powerful. It’s our responsibility to teach students how to use them meaningfully, while protecting the sanctity of focused learning time. Your middle ground feels like a hopeful path forward.

Thank you so much for sharing your classroom experience, it really highlights the complexity of this issue. I love the idea of “Tech Time” as a structured, purposeful way to build trust while still maintaining focus. Your reflection affirms my belief that balance, not extremes, is key. Phones are powerful tools, and with the right guidance, students can truly learn how to use them meaningfully. I appreciate your thoughtful insights!

Thanks so much for sharing your honest and balanced take on mobile devices in the classroom Nofisat. I really appreciated how you explored both the distractions and the potential learning opportunities.

As a fellow teacher, I completely relate to the internal tug-of-war you mentioned. In my own blog post, I shared that while I used to feel pretty confident managing devices in my classroom, the recent province-wide ban has actually made things harder. Now that phones are forbidden, students just find sneakier ways to use them, slipping into bathrooms or hiding under desks; and I’m still left managing the same issues, just in different places.

I love how you emphasized the need for balance and clear expectations. Like you, I believe there’s value in teaching students to navigate technology responsibly instead of removing it altogether. It’s not just about control- it’s about preparing them for the world they’re already living in.

Thanks again for the thoughtful read!

Thank you so much for your thoughtful comment. I appreciate your insights and shared experiences!

Hey Nofisat!

I enjoyed reading your blog! Your opening question “Are we protecting students’ learning environments by implementing these bans, or are we stifling their ability to thrive in a digital world?” perfectly describes my similar struggle with this topic!

I appreciate your thorough summary of the pro-side research; I, too, found these articles in support of a cell phone ban quite convincing, especially the TedTalk. As someone who voted against a cell phone ban, the readings Maherun and Kritika provided challenged my views. That said, Sadi’s debate points and research brought me back to my initial opinion: teach, don’t ban. I agreed with her point that educators are responsible for educating kids on cell phone usage.

I agree with your conclusion that a ban is a ‘band-aid’ solution and do not think it will solve cell phone use-related problems long term. I ended my own blog post restating that I am ultimately against a cell phone ban, and see the merits in teachers creating their own strong procedures and boundaries around cell phones in schools to support learners with their devices. I like how you ended with two practical strategies you feel will help. Thanks!

-Teagan Bryden

Hi Nofisat

Your blog is thoughtful and engages both perspectives. Your integration of empirical evidence, personal reflection, and policy examples makes this a compelling read. I was particularly intrigued by your reference to Jonathan Haidt’s TED talk framing of smartphone overuse as a “public health emergency.” This is a reminder that this isn’t merely a classroom management issue. This solidifies the point that responsible usage should be taught.

Like you, I concur with the idea that banning phones may not develop the digital citizenship skills students need to thrive beyond school. The studies you cited by Thomas, O’Bannon &Bolton, and Clayton & Murphy beautifully illustrate how mobile phones can be harnessed to foster collaboration, critical thinking, and creative output.

Finally, through professional development, teachers can better support responsible phone integration, especially in under-resourced schools. Here’s another interesting article on topic of technology integration.

Thank you for sharing such a balanced view on the topic.

~Sadi

Thank you so much for your thoughtful comment. I appreciate your insights and shared experiences!

Thank you so much for your thoughtful comment and your kind words. I appreciate your insights and shared experiences!