Reflecting on the 9 Elements of Digital Citizenship this week, the importance of synergy between the 9 elements became crystal clear. Without implementation of all nine elements, the entire system falls out of balance.

This being said, my focus for this week’s blog is how difficult it seems to be for educators themselves to utilize the nine elements in a way that best suits their own unique situations. It often feels as if the teacher autonomy necessary for full implementation of all nine elements is taken away and many aspects of digital citizenship are dealt with at an administrative level. The ability for educators to make professional decisions regarding these crucial nine elements is severely limited – and leaves very little room for professional autonomy and working with the diversity of student needs in our classroom.

“Digital Access” is one that comes to mind most immediately in my world of education. Ribble defines digital access as equitable distribution of digital technology and resources. My school division has recently announced their interest in conducting a rollout of 1-to-1 student devices in the division. In other words, a division laptop provided to every student. After some of our discussions in class this week, this initiative is beginning to sound very familiar…

One of our greatest difficulties and therefore lessons from pandemic teaching was of course digital access. The lack of access to technology (which at that time was absolutely essential to participating in the school process) was extremely worrisome for many of the students at my school. This lack of access certainly disproportionately affected our marginalized groups of students. For these reasons, I definitely do see the benefits that a 1:1 student device initiative would have.

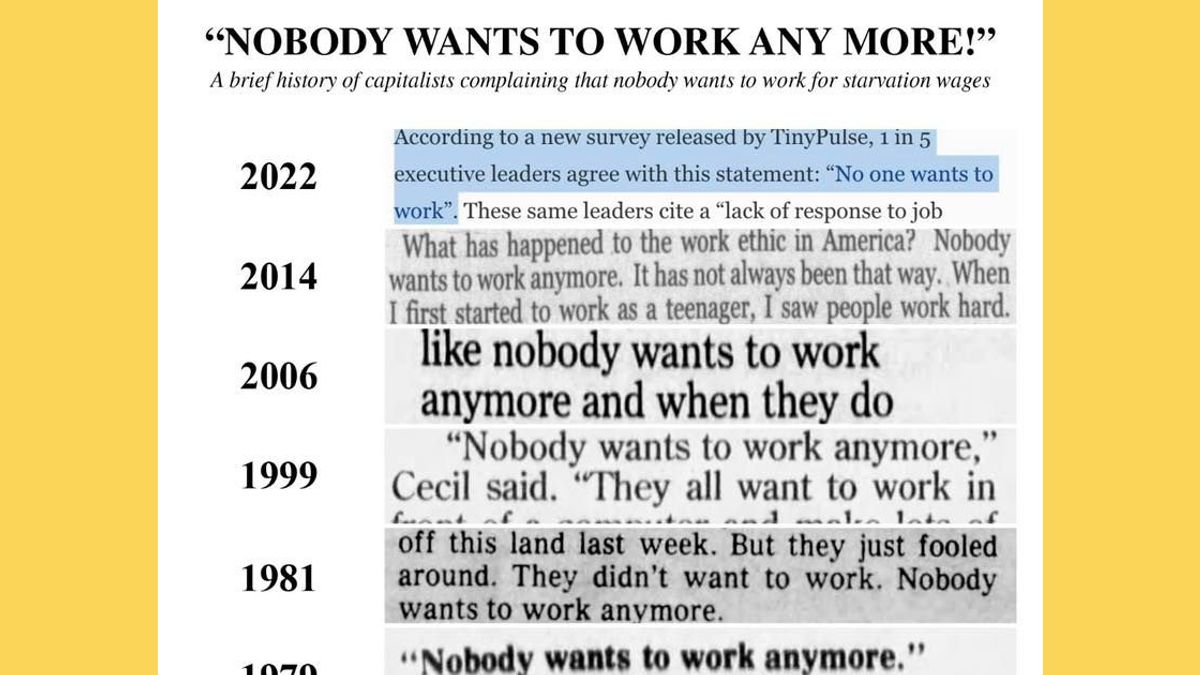

At the same time – I have discussed with other colleagues in the class in the blog comments the seemingly increasing problem of “throwing technology at the problem” within our education system. Without the proper structure and motivation, these initiatives seem destined to end up in a similar position to the “One Laptop Per Child” program discussed in the link above. It is also a hard sell for teachers – we are surrounded by swelling classrooms, crumbling infrastructure, and ever-growing pressures. It might be difficult convincing educators that this type of policy is where our money is best spent. I’m not sure exactly where I fall on this divide, but I do think it is important to recognize that educators themselves are the best consultation on something like this. Talk to the people on the ground floor!

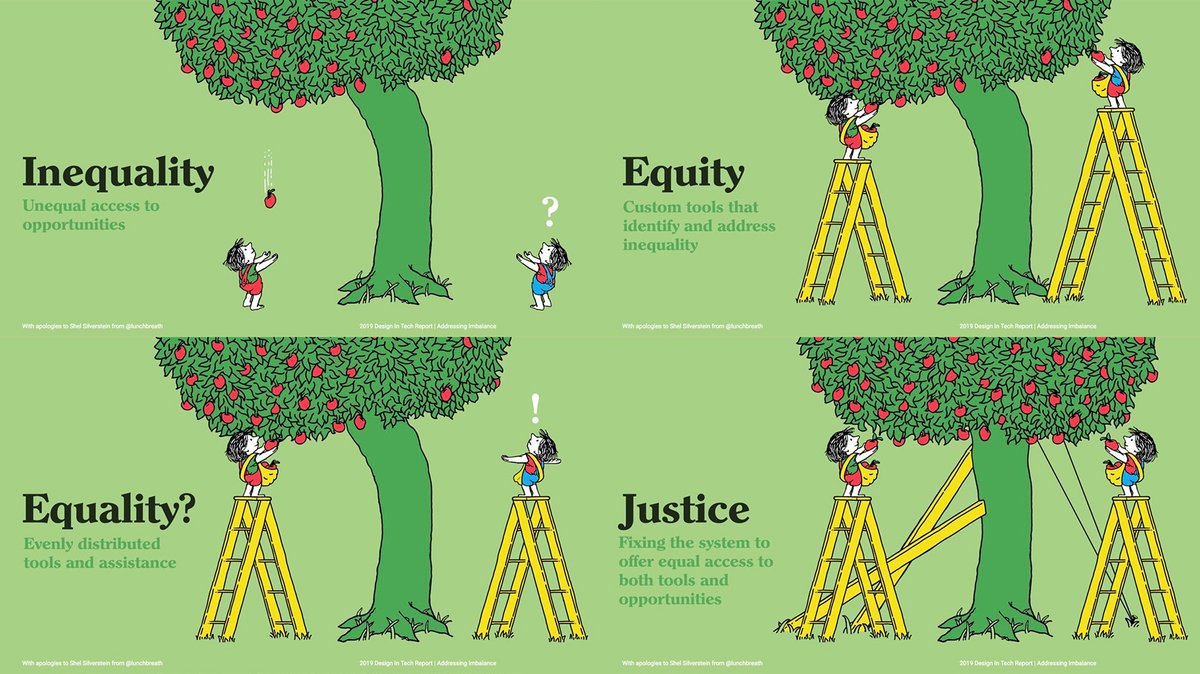

One last piece on this laptop initiative – going back to Ribble’s original definition, he calls for equitable distribution of digital resources. Not equal, but equitable. Is providing a division-mandated computer for all students an equitable distribution? Food for thought.

Thinking about these elements being implemented in my classroom, I come back to this focus on teacher autonomy. One way that I see Digital Access, Etiquette, and Health and Welfare all wrapped up into one tangible and very pertinent example is with school cell phone policies. These policies often range from teacher to teacher, school to school, and division to division.

For me, these policies are another example of how implementation of digital citizenship is moved from the classroom to the board room. Our division implemented a division-wide cell phone policy last year, with the idea to standardize practice across all schools. Interestingly, the justification that they provided for this policy mainly revolves around studies linked to digital technology and student mental health and well-being. Our division policy essentially states that cell phones and devices should be parked away from students at the beginning of class time. Teachers have the authority to allow access to devices for educational purposes.

What intrigues me about this policy is the wide range of reactions and levels of implementation between teachers. Some teachers praised this policy as a god-send. Others decried it as taking away student freedom. Some teachers follow it to the letter of the law. Others can’t be bothered.

My main thought is this – what implicit messages (good or bad) are we sending to our students through our implementation (or NON-implementation) of this policy? How does the removal of access foster digital citizenship? For me, it seems as if a policy such as this removes one element (Digital Access) in the hopes that other elements (Etiquette, Health and Wellbeing) can be improved. This seems contradictory – I began this post by recognizing that a balance of the elements is what’s needed to foster citizenship.

And finally – how does the creation of these policies that come from a higher level authority affect the professional life of us as educators? Lots of questions, not a lot of answers. Looking forward to hearing from you.

![Has science gone too far? [pic] : r/funny](https://external-preview.redd.it/Mce_BBf9h1gdK38cpkmXe23TsAN9Ro_HZLO3ukuBALY.jpg?auto=webp&s=264af5e5371e4c215da3d26e05eef49ad02aaafe)