I really enjoyed this week’s readings and discussion on the generational and cultural considerations that should be made when thinking about digital and media literacy. I think that the discussions we had in class and the posted readings and resources demonstrate the often foolish endeavor of generational generalizations – an endeavor that does a great disservice to both teachers and students alike.

The article “The Persistent Myth of the Narcissistic Millennial” was really well constructed. I thought it did a great job of disproving these generational generalizations that have become far too common place. Specifically, the article points to the idea that many of the studies and research used to justify false claims about millennials (and other generations for that matter) are simply doing bad science. For instance, I can’t stop thinking about a major flaw in the methodology of not only this weak research but also popular thought – and that flaw is that from my perspective, ALL young people are narcissists. It’s baked into the system! Young people of any generation deal with psychological complexes such as the spotlight effect that distort their thinking and alter their behaviour. This is not a generational problem, this is older people looking at younger people behaving as young people tend to do and lacking the hindsight and self-awareness to realize what’s really going on.

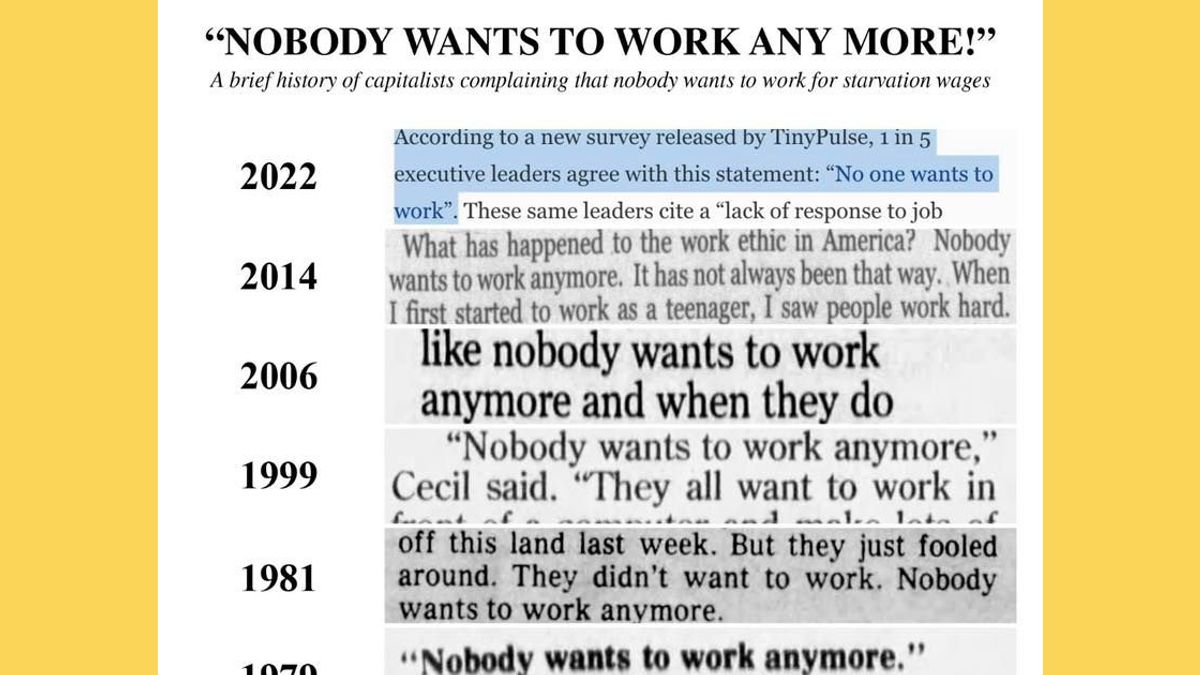

In our class discussion this week one of the generational stereotypes that we lamented was the oft brought up trope of millennials/gen z being lazy. The classic line we hear again and again: “nobody wants to work anymore!”

This leads me to one the questions asked on our course page this week regarding the future of education and our future generations of students. We are asked to consider what world we are preparing our students for. When I think of the false idea of laziness discussed above, I can’t help but think – if this was true, and nobody did want to work anymore – who could blame them?

Modernity’s punishing effects on the working class through the capitalist system mean many of us experience doing more work for less compensation. Our students, just like generations before them dating back to Gen X, face a future of economic uncertainty that will most likely lead to them being in a financial situation that is worse off than their parents’ generation, a story we have heard before. In addition, Ethan Mollick’s article on the role of artificial intelligence in the workforce places even greater question marks on the future our current students have to face. If “consultants using ChatGPT-4 outperformed those who did not, by a lot” (Mollick, 2023), who can tell what the role of even more advanced artificial intelligence in five to ten years time will be. And what will that leave for our students?

To be clear – I am not suggesting that our education system should be looked at as simply a student-to-worker pipeline. I feel very strongly in the opposite direction. However, a simple look at our curriculum and the priorities of our leadership tells us this is what many of those in authority positions see education as. And if this is the case, what is the place for all of these potential “workers” in an AI future?

As a side note: check out this part of a video from Tom Scott discussing where we are on the “curve” of AI technology, and why that can be hard to predict. Are we somewhere near the peak of what AI is capable of? Or are we merely at the beginning of a long acceleration in AI enhancement?

As I begin preparations for my content catalyst assignment, I am choosing specifically to look at the future of what we call “media literacy”. The question on our course page regarding proper citizenship in the future has me thinking even more about the idea of media literacy in the emerging future. The discussions we’ve been having around generational ideas reinforces the ideas set forth in the various “future of education” readings posted this week. While we look to the future and grasp at answers, the best we can do is cast out educated guesses and hope for the best. Were many educators concerned about the rise of AI and its implications for education even a mere five years ago? It doesn’t seem so. What horizons lay ahead that are just out of our collective vision?