As an Indigenous person, I play a vital role in this journey to reconciliation. I want to be clear on this critical role. I do not need to reconcile with my people. Reconciliation with Indigenous people is a goal designed to remove the systemic and social impediments that have been purposefully inflicted onto Indigenous people with the goal of ultimate assimilation. I have been a victim of these impediments, and they have had direct consequences in my life. Therefore, my role in reconciliation is not recognition. It is helping non-Indigenous people recognize this disaffection. As educators, we sit in a position of great privilege. We get to use our influence and our innovation to create a series of methods that will instill in our youth—the next generation, fundamental skills, knowledge and wisdom needed to see the journey of reconciliation come to fruition.

Before discussing the topic of reconciliation, we must first examine the need for reconciliation. To keep this paper concise, I will only discuss the need for reconciliation in the context of Indigenous discrimination and disaffection in educational history. The residential school system was catholic run, government-funded educational institutes with a student demographic of purely Indigenous students. The goal of these schools was to strip Indigenous youth of their culture, dignity, integrity, and remove their historical knowledge. By doing these vile atrocities, the federal government forced Indigenous assimilation into the white man’s way of thinking and being.

Beyond residential schools, Indigenous people have historically seen little representation in their schools. In the majority of cases, classrooms are dominated by white books, white music, white stories, white walls, whiteboards, and white teachers. Thereby creating this non-hospitable environment for Indigenous children. When Indigenous children walk into a classroom and see nothing relatable to themselves or their culture, why would they feel welcome? They would not. This creates a sense of animosity Indigenous children feel from white children and contributes to the Indigenous education statistics, which show Indigenous students are less likely to graduate.

When addressing reconciliation in the concept of education, we first need to recognize two things. Firstly, that the current educational system is predetermined to instill non-Indigenous ways of knowing, learning and teaching. This way of knowing is categorized as the I/It tradition, which I will summarize as resistant to change, culturally insensitive, and upholding the current institutions created by the eurocentrically dominated education system. Secondly, an Indigenous student cannot reach fruition academically unless their culture is fundamentally recognized in their educational setting. I have written a research paper for my Indigenous studies 100 class that extensively analyses cultural importance in youth. Through my research, I have concluded that the most critical element in Indigenous youth is their culture. Therefore, in order to be successful in our journey to reconciliation, we need to ensure that in every educational setting, an Indigenous student has reliable access to cultural resources. Some examples of these resources include Indigenous art present and visible in the classroom setting. Indigenous elders with a dedicated position/ office in educational institutes. Culture-sensitive lessons. Traditional Indigenous stories quickly and freely accessible in academic libraries. School counsellors that are competent in the field of Indigenous issues (traditional counsellors might not have the knowledge necessary to provide helpful counselling within the context of Indigenous-specific problems, trauma, and roadblocks).

The Truth and Reconcilliation Commission (TRC) establishes three key steps we can take towards our journey to reconciliation. All three are not steps I have laid out previously. This is because I view these steps as the bare minimum—simply not enough. While these steps are critical, they are not critical because of their impact. They are critical because they are the easiest to do. It is easy to acknowledge that this is traditional Indigenous land, it is easy to fly a flag. True reconciliation needs much more in order to be fruitful. The TRC also acknowledge that these are “little things”. It is defeating for Indigenous people to have to establish this bare minimum, but as mentioned it is vital we do so.

Peggy Mcintosh’s paper on white privilege describes various ways Indigenous people are disaffected in society both in and outside of educational settings. As an Indigenous person I read her paper with a grain of salt. While it makes accurate points in the area of white privilege, she compares this to modern day feminism. It is irresponsible to draw comparisons between racial disparity and gender disparity. Which is why I am skeptical of her paper, because everything she states was only brought to light because of her beliefs on gender equality. In particular, number 13 on her list of white privilege manifestations she states “I can speak in public to a powerful male group without putting my race on trial”, again I see comparisons to an unrelated issue. Why is it important to include male in this context? I definitely see undertones of an ulterior motive that is not aligned with reconciliation within the making of this article.

My skepticism aside, she does make critical points in regards to white privilege, as an Indigenous person I will highlight the ones I believe are most vital in an educational context using my experiences as an Indigenous student:

Number 7. “I can be sure that my children will be given curricular materials that testify to the existence of their race.”

Number 12. “I can swear, or dress in second-hand clothes, or not answer letters, without having people attribute these choices to the bad morals, the poverty, or the illiteracy of my race.”

Number 15. “I am never asked to speak for all the people of my racial group.”

Number 16. “I can remain oblivious of the language and customs of persons of color who constitute the world’s majority without feeling in my culture any penalty for such oblivion.

All of these listed are ways I have felt uncomfortable during my elementary and secondary academic career. These experiences influence my proposed ways of ensuring a healthy, hospitable environment. I have used my experiences and what I believe would have helped me become a more successful student. Which is my responsibility in the journey to reconciliation, to use my experiences to assist the educational administration to provide the resources necessary to teachers in the effort towards the ultimate goal of meaningful reconciliation.

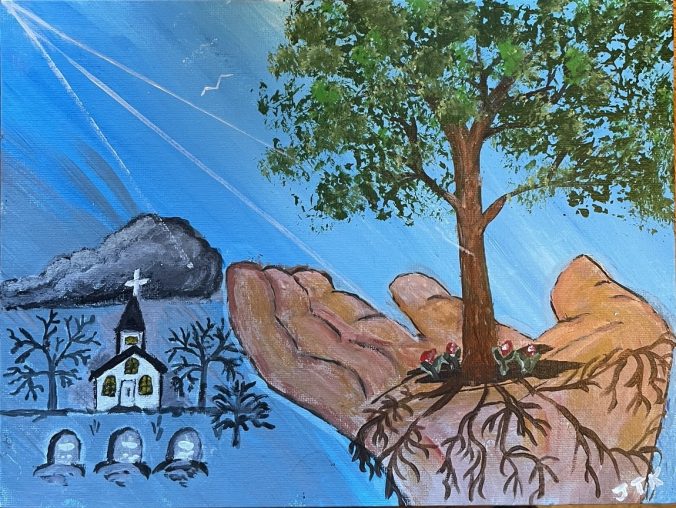

Everything I have written in this paper is to provide a substratum to the aesthetic component of this paper. My aesthetic piece is a painting that depicts a dark, melancholic past we as Indigenous people have experienced. Then the hand holding the tree is a symbol describing our role as educators in the uplifting Indigenous people. We hold the ability to create healthy Indigenous youth, and bring together this world of racial equality, so that ultimatley we can share this land as brothers and sisters of equal standing.

References

Bearhead, C. (2015, November 25). 94 Calls to Action, 3 ways to get started | Illuminate

Faculty of Education Magazine. Illuminate Faculty of Education Magazine. https://illuminate.ualberta.ca/content/94-calls-action-3-ways-get-started

Mcintosh, P. (1989, July). “White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack” and “Some Notes for Facilitators.” National SEED Project. https://nationalseedproject.org/Key-SEED-Texts/white-privilege-unpacking-the-invisible-knapsack

PD_Module 8: Reconciliation. (n.d.). Reconciliation Education. Retrieved March 9, 2022, from https://info.reconciliationeducation.ca/module-9-reconciliation

Pirbhai-Illich, Fatima & Martin, Fran. (2019). “A relational approach to decolonizing education: working with the concepts of invitation and hospitality”.